I : The Answer.

With everything my eyes have seen, in the many years I have spent living in Europe, about the near-pathological disposition of white people as a collective, less particularly as individuals, towards a race-based view of the world;

And, with how that stunning realization has cleared my eyes of all the fàbú by which I was raised;

I have at several junctions been disappointed in the generation that came before us: namely, our parents, and our teachers.

I have been disappointed in them, because they hid the truth.

They did not do enough to warn us, considering the alarming scale of how race & racism envelop everything, and determine how the world relates to us, and us to them.

Nearly all of my professors, consultants and teachers at the University of Ibadan, and particularly at the College of Medicine, trained in Europe or America.

Very many of them constantly regaled us with legends of how great they became overseas, until it was a matter of fact for us children and students to aspire to replicate their adventures.

Most of my class now lives in Europe, America, Australia etc: most medical students barely hit the ground from graduation before jápáing to specialize and practice abroad. We finalize our USMLEs and other foreign qualification exams before we’ve even taken our Ibadan finals. Our UCH is just an airport where we wait to board the Jápá Airways. Our medical education is just a ticket to travel. I’m not saying this is good or bad, although Nigeria has a statically high burden of medical brain drain. My focus is that from the moment we set foot at the matriculation ceremony, our eyes are set on jápá.

Today, decades later, I still vividly recall sitting on the steps at the entrance to anatomy department of U.I., with my sophomore colleagues, our white coats stinking from our first experience in the cadaver room, and we were already discussing jápá. My friends had already made up their minds about which country, what exam, which specialization.

For some reason, I couldn’t relate. Nigeria was the limit of my satisfaction.

At the end of my medical school, we had that discussion again.

By this time, half my class had taken the USMLE certification, and they were tossing these jargons around: “Step 1! Step 2!”… but I was clueless. I had no plans, no intention.

I think this unusual lack of jápá ambition was down to my socialization, and how secluded I was from mainstream cliques. The urge to jápá was inseminated into our pulsating brains every single day we attended a lecture, clinic or ward round. There was always one Professor So and So, whose reputation went before him, or her, and all the hallways were soaked with legends of how he or she was a god who had conquered Harley Street and Harvard, and deigned to return to Ibadan to share some of their greatness with us mere mortals.

Our young eyes were filled with dollar signs, but not so much as our hearts were possessed with the desperate urgency for this kind of peerage and prestige.

I’m telling this story to say there was nothing in the narrative about difficulty, or hardship, not to mention racism. It was all about clout, an inbred aspiration to join the uber elite, and keep up with the upper-middle class jápá tradition, as our elders had done before us.

Greener pastures is a well-trodden Nigerian idiom.

Abroad is greener pastures. But Naija ? It’s just dry grass, like Sambisa.

Fast forward many years.

I too live in Europe. The Netherlands to be precise, though I’ve been nearly everywhere else.

In fact, in my Àjàlá life, I have 30 countries under my belt. And counting.

Airports now make me sick.

When I first came to Europe, my eyes were filled with wonder. Not in that boopic, mouth agape way, no. Just a mutual appreciation of how well things were done, and a constant projection of those standards back home to Nigeria. “Oh look at the train. Oh look at this expressway. Oh look at that internet service. We should have that in Nigeria.”

That was my daily mantra.

At the same time, I was proud of Nigeria.

I had just ended a 7 year run of living in the best parts of Abuja. My life was a privileged one. I had cars and houses. Money was not my problem. Whatever Buhari and Atiku enjoyed, I was there. Jacuzzis, wines, four courses, designer things, expensive gadgets, and bitches.

Ok no bitches.

But really.

So, I didn’t leave Nigeria because it wasn’t working.

I left because, love. And I loved Europe, as I loved Nigeria, although I think I always loved Nigeria more.

But, it didn’t take Europe 5 years to teach me the love was not mutual.

One calamity after another, they took everything away from me, and by the time they were done, they had made it clear that no matter my pedigree or prestige, I would never be enough.

This is not where I tell those stories. You can buy my 5 biographical novels and read my 25 published essays for that, right after I am awarded the Pulitzer and the Nobel.

All I have left is life itself.

And since I didn’t die, stories will be told. And I will be rich. Again.

Like many other people who are considered anti racists, or racial justice activists, the question that keeps coming back is, “What radicalized you?”

No African becomes race conscious because they read it in a book.

You have to be broken first. Your dreams burnt to ashes. Then you wake up and say, OMFG. And you finally see the world, not as my professors in Ibadan said it was, not as all my USMLE-pursuant classmates dreamed it would be, but as it is: systemically bloody, deliberately unjust, brutally unequal, and racially profiled, from the water you drink to the air you breathe and everything in between.

If you think I’m exaggerating, go away: this post is not for you. Go back to reverie & seance.

II : The Question.

The question I want to ask is, if race and racism are central to everything we do, every day, from Abakaliki to Alaska, from Zurich to Zungeru, then why did those who went before us, blind us with such saccharine, soporific, soapy western propaganda?

Look, I want to be compassionate to my parents. After all they are my parents. And my teachers. After all, our culture is one of respect.

But I will ask the question.

Then I will parry the answers away from blame, to maybes.

Maybe they were trying to protect us? To protect us from harsh reality?

Maybe they didn’t want to discourage us?

Or, Maybe, they were obstinate capitalist elites who couldn’t see beyond their own egos and who reinterpreted the world to suit their delusion that we as Africans have all it takes in this world to be just like our colonizers?

Maybe, maybe.

You know, colonization is a trauma. It bleeds the brain. And it bleeds into the brain.

It swells inside, and cuts off breathing, and drowns consciousness in coma.

And then, the only pain relief is to imagine your way out of it.

Imagine religion. There’s a heaven somewhere. And everything is better there.

And we can forgive the past away.

Imagine western education. If we read enough books, we will be just like white people.

Which is how our elites imagine their way up, until they colonize us, just like white people. And the cycle continues, and we inherit ways of thinking and being, and we inflict patterns and systems on generation after generation, and nobody says “Stop!… it’s not true. You’re in a coma. Reality is different!”

Nobody says stop.

Every generation promises the next that when we become white, we will be okay.

And the delirium continues, drip by drip, world without end.

Amen.

In closing, I want to converge on Professor Tomori.

Erudite and esteemed, distinguished Virologist, polio expert, Lassa fever expert, yellow fever expert, Ebola expert, Covid don, former Regional Virologist for the World Health Organization, Member of the Strategic Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE), Board Member Gavi Vaccine Alliance, and pioneer Vice Chancellor of Redeemer’s University.

Whew.

I’ve always loved Professor Tomori.

He’s my dad’s friend & colleague, both Professors in infectious and viral disease specialties. His kids are our friends, we all schooled together in a pool of future professors soaked in the sweat and success of our distinguished parents, the Ibadan elite.

But.

And it breaks my heart to say, but last week, I watched this great man in an interview with Arise News, where he emphasized that race was not the problem with how Covid was being managed.

He spluttered it like it irritated him to have to address such a distraction: “it is not race, or color, or anything like that!”

This was in the wake of a round of globally viral interviews with Dr Ayoade Alakija.

She is the co-chair of the African Union’s Africa Vaccine Delivery Alliance.

Alakija has been quoted in several televised interviews, op-eds and social media posts, rebuking the west for hoarding vaccines, then singling out Africans for knee jerk travel bans which have no basis in science.

When I listened to Professor Tomori stridently play down race, I felt he had been triggered by Alakija.

She’s half his age, and she’s platforming a new and different narrative. Many people my age are excited about Dr Alakija. Even scholarly journals nowadays are replete with reports and studies about the rampant abuse of science and medicine by racism.

We are happy to have someone in authority finally speak out.

But Professor Tomori is uncomfortable. Not just him, many educated middle class Africans in his generation.

The same class of Africans who idealize the colonial era as the Good Old Days.

Emerging evidence weeks later actually confirm that the latest variant evolved from Europe, and is dominant in the West: yet, there is an exclusive, blanket ban on Africa.

Most people agree that this clampdown is stigmatizing and based on colonial racist views of Africa as the continent of problems, and the continuation of a pattern of antiblackness in global relations.

But Professor Tomori reiterated his rebuttal of the role of race in the global heath response just this Monday, in another speech at the national summit organized by the presidential steering committee (PSC).

Twice during the speech, while explaining that the real problem was not race, but corruption and selfish interests, the renowned virologist broke down and wept, evidently passionate about his experience of the system he was describing. He ended to a rousing ovation.

Professor Tomori is not wrong about his diagnosis of corruption and selfish interests.

But he is wrong for wanting it to be true at the expense of racism, and its modern manifestations in the global neocolonial order.

We don’t have to take a stand of mutual exclusivity, a binary view, an either-or.

We can see both realities. Our systems are corrupt. And, we are in a racist global order.

III : The Challenge

This was the crux of my thinking this morning, as it has been repeatedly, for several years.

If I could advise the generation of Professor Tomori, and the government officials and heads of agencies who listened as he spoke from the heart, I’d ask them not to choose one diagnosis at the expense of the other: our development problems don’t have to be only due to corruption, and they are not only due to colonization.

They can be due to both, and more importantly, they actually are.

About corruption in particular, it has become a trope, an easy answer, actually promoted and propagandized by colonizers themselves, to deflect conversation away from their culpability in the roots of the system African countries have been run by since 1886.

Before colonization happened nearly two hundred years ago, “West Africa was the home of more kingdoms and empires than any comparable region in the world.

All these numerous countries, kingdoms and empires had varying political and social systems. In what is today Nigeria, we could see (precolonial) democracy in action, with the first global emergence of electable governors. Advanced political organization was seen here, in these parts, as well as ingenious medical practices and technical skills.”

I’m quoting from pages 68-51 of ‘The Black Past, A History of African People (Tyrone Smith, 2021)’, a thoroughly researched and appendixed compendium from 12,000BC till today.

Shall I go on?

“This West African region was perhaps the most industrious and prosperous region of the time, with the highest concentration of highly developed societies on the continent – and quite possibly the whole world!

There, we find incredible artwork with qualities that would be considered contemporary if not for their production dates. Incredible monuments were built, including cities that were larger than most of the present day, and feats of architectural and engineering genius were widespread.”

I go on?

“The three largest empires of West Africa created a Golden Age not seen since the New Kingdom era of Kemet (ancient Egypt).

And, incredible riches and fantastic universities were found there from 10-16th centuries.” End of quote.

That is a picture of what West Africa looked like before we were interrupted and overwritten by colonization. There’s a reason you won’t find this depth of research in Encyclopedia Britannica. It’s the same reason Professor Tomori’s generation keep telling us colonization was the best thing that ever happened to us.

To overcome a Eurocentric rewriting of history, which erases ‘inconvenient’ parts, you have to do the hard work of collation from several sources yourself, but you also need a deep-seated motivation to pursue an alternative to the dominant narrative.

Only last week, an example of the habit of colonial erasure in education and history went viral: an exaggerated world map that shrunk Africa and bloated the West and the rest.

But, why did they teach such a deliberately wrong version of geography for 100s of years?

Who gains when some people are amplified and others made to look, and feel smaller?

Nobody is saying Africa was once perfect.

We are saying colonization was an interruption, and as empires rise and fall, within a few hundred years, even our present reality will be consumed.

Hopefully, our own history, and geography, will not be maliciously distorted to oncoming generations.

In closing, there are symptoms in medicine called visual field defects.

It means a patient can only see a partial view: for example, maybe what is in front of them, while their ability to see things that are to the outer, more extreme portions of their field of vision, is impaired.

Many of our parents and teachers, see the world that way.

They cherry pick the parts that are convenient, and leave out any uncomfortable information.

Like I argued earlier, maybe they did it to protect us from the unpleasant reality.

But our own generation’s inherited inability to see the world clearly, is now hurting us.

If we include colonization in our calculations, we will understand the propaganda to force corruption as a uniquely African problem, the omni-answer to every development problem.

You know, just this year the entire Dutch cabinet was sacked because they defrauded nearly 30000 families, mostly black and brown ethnic minorities, in what is called a “shocking tax scandal”. The Netherlands is also in the top 5 globally in fleecing developing countries of $50 billion of revenue through illicit tax outflows, and is the 2nd largest enabler of global corporate tax abuse among OECD countries.

You won’t find that on CNN. But you can Google it. And all the other ways the narrative of western meritocracy versus African weakness is fostered.

If we include colonization in our calculations, we will understand that corruption is not the cause of underdevelopment.

Corruption is a sign of underdevelopment. Itself is caused by something, and that something is structures & systems, and our structures & systems are colonial, and have been since the global & regional civilizations that once flourished all over Africa were erased, then replaced.

So, we will not rise by focusing on eliminating corruption and voting in good governance alone.

We will also have to deal with the global mathematics. The equations of neocolonialism multiplied by global capitalism, to the power of white supremacy.

And the common denominator is race. It’s everywhere you look, and it has been so for almost 400 years, since slavery.

Racism is our burden to unpack, and nobody is going to teach us except us, because those who write the books we read still benefit from the global order that privileges them at our expense, and exploits us for their advantage.

Until we awake out of the long slumber induced by generations of colonial miseducation, all our permutations for development are like a child inside the womb who has not yet seen the world, yet tries to describe it.

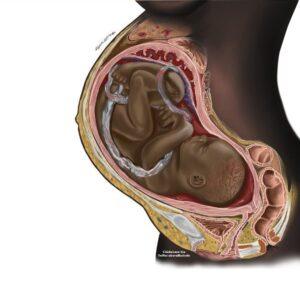

And so, I close with this pioneering photo, illustrated by Chidiebere Ibe.

A medical student and aspiring neurosurgeon from Nigeria, his illustration of an unborn child in the womb went globally viral since last week, with many commenters confessing that in several decades of learning and practicing medicine, they had never seen a black pregnancy depicted.

Ebere’s groundbreaking illustrations have been published in not a few journals, and he can be followed on Twitter and Instagram as @ebereillustrate, and he’s part of a younger generation of Africans who are kickstarting essential conversations, to remove generational causes of ideological astigmatism from our worldviews.